How to Figure Out the True Cost of a Manufactured Part?

Manufacturing companies in today’s global economy rely on an intricate network of global and local suppliers. With typically more than 50% of operational cost is tied up in their supply chain, manufacturers must closely manage and continually optimize supply chain operations, balancing quality, cost, risk and resilience.

Research shows that in a typical manufacturing company, as many as 30% of purchased parts are not priced optimally: either suppliers are charging excessively for parts that can be sourced elsewhere under more competitive terms, or market competition and aggressively negotiated supplier contracts have resulted in lower quality parts and greater supply chain risks. Furthermore, it is common to find identical parts sourced in small quantities from multiple suppliers, reducing negotiation leverage, bloating inventories and introducing further waste into the supply chain.

In some markets, multiple vendors and strong competition may suffice to drive down prices and ensure high quality and level of service. But in markets where there are only a few suppliers, buyers’ options are limited and optimizing supply chain decisions can be difficult.

While these challenges are well recognized, making effective part sourcing decisions and negotiating optimal pricing aren’t easy, and most manufacturers do not have an objective and consistent means to rationalize supplier relationships.

The ability to determine the true cost of a part in a systematic fashion gives both manufacturers and suppliers critical tools that should be utilized during design, sourcing and bidding activities. Below are some use cases and examples of how “should cost” analytics can be used during key product lifecycle phases.

Supply Chain Optimization

As stated in the foreword, more than half of operational spend of large manufacturing organizations is tied up in the supply chain. Reducing the number of suppliers and optimizing contracts for each supplier’s capabilities can help companies reduce supply chain waste, manage inventory costs and improve overall operational efficiency of their supply chain.

Everest Institute research estimates that companies can achieve 22-28% cost savings by utilizing their existing supplier base instead of adding suppliers and rebidding contracts:

- 35-40% one-time cost reduction by avoiding setup and on-boarding

- 20-25% reduction in operations and internal overhead

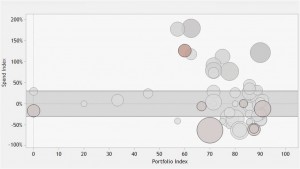

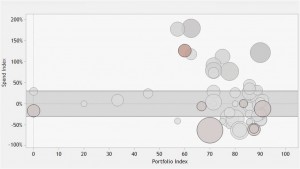

Akoya, a part-costing data analytics software company, conducted an analysis of cast parts at a large manufacturer of heavy equipment. The analysis of 1,137 cast parts from 39 different suppliers showed that 24% of the parts were priced 25% or higher than they should. The analysis revealed that selecting lower cost suppliers and renegotiating fair prices for those parts would result in annual cost savings of approximately $21M. The figure below is of a typical analysis, showing clusters of similar parts that are priced above or below the average for that class of parts.

(Source: Akoya)

Bidding and Contracting

Shifting the discussion from buyers to suppliers, many suppliers do not have a systematic and reliable method to estimate the cost to produce a product. All too often they resort to a ballpark cost estimate and adding a lump sum percentage for overhead. In competitive situations, these suppliers may quote high price and lose the bid, or, potentially worse, their price will be low enough to win the contract but will a negative impact the profitability of the deal.

A data-driven analytic approach to manufacturing cost estimate reduces the time and effort to respond to request for cost proposals, provide accurate appraisal of actual cost and profit margins, and support the evaluation of design and manufacturing alternatives, volume pricing, and the like.

And the same approach benefits those that evaluate supplier responses: identify excessive price quotes – whether too high or too low – and help in selecting the best suppliers to conduct business with.

Product Design

Multiple studies that show that demonstrate that most of a product manufacturing cost is determined during early design phases have been around for decades, yet they are generally ignored until a cost takeout campaign is initiated, at which point the manufacturer has already incurred significant loss and the ability to optimize cost decisions is very limited.

Accurate cost information can be beneficial in a number of design engineering activities, such as:

- Input for manufacturing cost analyses, weighing alternative sources and manufacturing methods before the design is frozen.

- ECO management: assessment of cost ramifications of a design change or switching to a different supplier.

- Cost reduction / cost take-out campaigns.

What is 3D Part Cost Analytics?

The first question that comes to mind, then, is how to determine the true manufacturing cost of a part, especially if that exact part has never been manufactured before.

Advanced 3D cost analytics is based on a part’s 3D CAD model. By analyzing the key features of a design: dimensions, tolerances, weight, etc., and of the manufacturing processes: machining, drilling, heat treating, etc., and using a detailed database of various manufacturing processes, industry standards, and associated cost, analytic software can estimate the target cost of making a part based on the market price of similar parts.

Activity based costing is an alternative method for estimating part manufacturing cost. It identifies the manufacturing activities involved in manufacturing the part, such as casting, stamping, forging, drilling and finishing, and uses standardized labor, machinery and overhead costs to calculate the actual manufacturing cost of that part.

Market prices are derived from a broad range of sources. These include a company’s supply base, supplier catalogs, comparisons of supplier responses to bid requests, and company specific design rules and “should cost” target guidelines.

Both methodologies have value and can be used to complement each other. Whereas 3D part analytics focuses on a “bill of features” to identify like parts, activity based costing uses a “bill of activities” to do the same.

Recommendations

Instead of the periodic but infrequent cost takeout and supplier rationalization campaigns, manufacturing companies should employ “should cost” analysis as an ongoing best practice. Using a structured approach and analytic tools, manufacturers should be able to introduce cost and supply chain consideration earlier in the product design, negotiate fair prices with their suppliers, and achieve greater efficiency and risk resilience in their supply chain.

“Should cost” models are not designed to be completely accurate, nor should they be used as the only decision criterion in selecting a supplier. They need to identify areas of cost optimization opportunities and help identify and assess alternatives for cost savings and supply chain optimization.

Not all manufacturing costs are controllable. A “should cost” analysis helps identify areas of cost that can be improved such as over-specification of tolerances is a major driver of cost. The analysis can identify existing designs and inventory parts that can meet the design specifications – possibly restated – at lower cost.

Obviously, an optimal design and efficient supply chain aren’t only about driving suppliers’ cost down. In fact, over-leaning the supply chain by focusing on lowest cost suppliers, pressuring supplier profits, and implementing very lean just-in-time inventory strategy will likely introduce unnecessary risks and result in a fragile supply chain.

Suppliers can be a great source of cost reduction innovation. This is a significant source of cost savings, and one that is typically overlooked by traditional procurement organizations.

Why Now?

This topic isn’t new. You can find blog discussions dating back several years that followed the regular hype cycle of analysts and bloggers discussions: they start in a flurry and then die very quickly so we can free up the blog space for the new hot topic de jure. But two recent acquisitions might bring conversations on “should cost” analytics and other PLM activities that were relegated to a back seat role. In March, Akoya, a “should cost” analytic software company was acquired by I-Cubed. Subsequently, I-Cubed’s PLM business was acquired by KPIT, an India-based global IT consulting and product engineering company.