Does 3D Printing Doom the Supply Chain? Does it offer new business for carriers? See conversation at Supply Chain @ MIT: http://supplychainmit.com/2013/07/18/does-3d-printing-doom-the-supply-chain/

A recent CIO Magazine article offered a perspective and guidance on how to “Avoid Mobile App Failure.” Not that we expect much depth from CIO Magazine, but this one-page piece, based on advice from a couple of industry analysts, reads like any other tired project management 101 guide: develop a roadmap, secure a project sponsor, do a pilot test, get user feedback, etc.

But the topic itself does beg a question: Is there a fundamental difference between developing a mobile application and deploying other types of end-user software? Is it true, as the author implies, that there are more challenges and failures deploying mobile applications than other types of software?

In recent years I have helped a number of end-user companies, software vendors and system integrators understand and exploit the opportunities offered by the proliferation of mobile devices and pervasive connectivity, as well as the associated challenges and risks. Here are five common mistakes they make.

Mistake 1 – The Shiny Object Syndrome

Companies and their IT teams are often lured by the media hype and fall victim to snazzy displays and cool user interfaces. They often forget to apply commonsense business measures to assess the value of mobile applications, and merely assume that just about any process and application – no matter how poorly designed or how little end-user value it might have – will be embraced by the users due to the fact that it runs on a “cool” device. They are, of course, wrong.

Mistake 2 – Do Think You Know Your Users?

Interestingly, some of the more commonly cited use cases for mobile applications offer very little value to end users. For instance, there are numerous examples of technical information delivered to a tablet instead of as paper manuals. Makes sense, doesn’t it? In reality, most assembly line workers and service technicians perform routine tasks and use manuals only rarely. Moreover, when they need information, they tend to prefer personal communication over searching for information, which tends to be too generic and out of date. Of course there are exceptions to this rule, so you need to select the use case that will provide tangible and credible end user value and assess the return on that investment.

Mistake 3 – Missing a Bigger Opportunity

Conversely, in their haste to port existing applications to a mobile platform, companies neglect to reevaluate existing processes and determine if and how they will benefit from the inclusion of mobile technology and is there an opportunity to restructure or even do away with suboptimal processes.

Mistake 4 – Underestimating BYOD

The BYOD (bring your own device) trend is accelerating. It appears that some companies are not only accepting it – they have little choice in this matter – but also embracing it, believing a BYOD policy helps lure millennials to the workplace and drive usage of corporate applications. These arguments have merit, of course, but BYOD also add complexity to systems management and create potential security and privacy liabilities, which the IT department may not be staffed to handle.

Mistake 5 – Who Needs a Corporate App Store?

Apple’s App Store is the envy of the industry, and, for some reason, companies believe mimicking that construct adds immediate value. The functional equivalence of an app store: a centralized repository of corporate-approved applications that ensure multi-platform compatibility and security compliance makes sense for IT. But in a corporate environment, the notion of apps: snippets of functionality designed to accomplish a very narrow task, each with a different user interface and workflow and no interoperability can often lead to process fragmentation and data gaps.

So here are my five steps to help you succeed in deploying your mobile applications:

- Define the unique characteristics of user applications deployed on a mobile platform, such as ubiquitous access in tangible terms and in the context of your business and user needs. Also consider potential downsides such as screen size, data security and BYOD management.

- Assess if and how deploying mobile applications will improve the current process or perhaps enable a new and better process. This is where most companies fail miserably. They assume, incorrectly, that porting an application to a mobile device will magically encourage users to use it more frequently and efficiently. The reality is that a poorly designed business process or an application with no clear end user value will not improve when ported to a mobile device; most likely, the opposite.

- Once you conclude that incorporating a mobile device has tangible value, redesign the business process, paying close attention to related processes and enterprise applications that may be impacted and ensuring application and data interoperability.

- Determine the appropriate App Store analogous that fits your business. Instead of disparate apps think about packaging user activities and business proceeds elements in user interface apps connected at the back end. For example: inventory lookup, individualized reports, or product inspection app, all connected to the back office ERP systems so that data integrity is maintained.

- Go back to CIO Magazine for the rest of the project managers handbook

Last year, the Obama administration finalized a new set of fuel economy standards that will require car companies to average 54.5 mpg across their fleets by 2025—the biggest change since the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) law was passes in 1975. Current rules for CAFE program mandate an average of about 29 miles per gallon, with gradual increases to 35.5 mpg by 2016.

Automakers are taking different approaches to meeting the increasingly more stringent guidelines. Electric drivetrain, both plug-in and hybrid, is one obvious approach. Consumers gravitating towards smaller vehicles is another. However, a significant portion of OEMs’ fleets will still be based on traditional gasoline powered internal combustion engines.

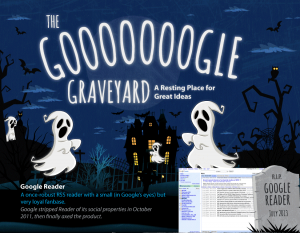

But automotive engineers are not at their wit’s end. The designers of Nissan Altima 2013 were able to achieve significant mpg savings through improvement by employing a newly designed continuously variable transmission, lowering overall mass and reducing drag.

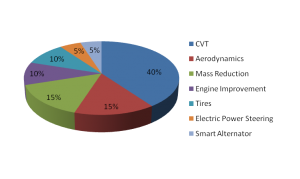

Although sales of electric vehicle in the U.S. in 2012 were much stronger than in the previous year, they were barely noticeable, accounting for less  than 0.5% of the 14.5 million cars and light duty trucks sold during the year. With some exceptions, public interest in owning EVs, seems to be dwindling.

than 0.5% of the 14.5 million cars and light duty trucks sold during the year. With some exceptions, public interest in owning EVs, seems to be dwindling.

A few years ago, General Motors decided to bet on electric propulsion as part of its recovery strategy, in part perhaps because worldwide sales of EVs, especially in China, are expected to grow over the next decade. GM elected to enter the market with the Chevy badge, targeting the demographic of market leader Toyota Prius, and planning to leverage the global presence of Chevy in future high demand markets.

Bob Lutz, the former GM Vice Chairman who led the development of the Volt often referred to the Volt as the most important product for GM. The Volt was brought to market in only two years, which is record time for a car with that level of technology innovation. Perhaps Lutz’s promise to finally retire once the Volt has been launched had something to do with it?

The Volt’s sales, while strong, are still well below GM’s expectations and far from being able to make a meaningful dent in the dominance of Toyota’s Prius. Trying to catch up, GM recently cut the price of the 2013 Chevrolet Volt by $4,000 and nearly doubled the production capacity of the Volt production line. But Toyota’s vehicles, including Prius and other hybrids, and the recently announced plug-in hybrid (PHEV), continue to dominate the market in the U.S.

So GM is signaling a change in tack and going to offer an extended range electric Cadillac, the ELR, presumably to attract more affluent buyers that perhaps prefer the luxary image of Cadillac. At the time, Lutz objected to it because of the lack of brand appeal outside of North America.

The problem with this strategy is that it positions the ELR awkwardly between the popular Toyota Prius and the media darling Tesla Model S, but with hardly enough reason for anyone to switch brands. A low cost Cadillac priced to compete with the Prius will also compete with the Volt, diluting the value of both badges and of the entire portfolio. GM is obviously delighted with the success of the rejuvenated Cadillac brand, but using it to save GM’s EV strategy isn’t such a good idea.

GM has to figure out how to deal with the growing strength of Tesla. Although Tesla sold less than 5,000 vehicles in 2012, it reported a 13,000 unit backlog and has the manufacturing capacity, presumably 20,000 units per year, to deliver it. The growth in Tesla’s market share will come from the same segment GM targets the ELR for.

However, GM has several advantages and opportunities to compete against Tesla’s cars thanks to its retail and service network, and the practicality of the range extending gasoline engine.

Tesla has to clear a number of hurdles before it can reach profitable market adoption outside the high income urban demographics. Currently, the company does not have retail and service network. Recently, Tesla recalled Model S cars manufactured between May 10 and June 8. The campaign required driving to a customer location to pick up the vehicle and to deliver it after the repair work. The company is also in an ongoing battle with NADA, franchised car dealers and state regulators to allow it to sell direct to consumers.

Also, despite Tesla’s ongoing efforts to build up its charging infrastructure, the practicality of the Model S outside these urban areas is still limited. Both the ELR and the Volt have a longer practical driving range that the Model S, because they can revert to gasoline when needed. The Model S can reach 300 miles with the largest capacity battery available. This means you can go only 150 miles or so before you have to turn back. The Volt can travel only 40 miles on a single charge, but with the auxiliary gasoline engine it can reach 300 miles although, obviously, the performance under gasoline engine compared to the Model S will be quite anemic.

GM should use the range advantage, coupled with its service network and the lower sticker price to drive sales and establish stronger brand presence, while Tesla is fighting court battles and building the charging infrastructure. The Tesla brand will no doubt continue to attract certain demographics, but the bigger market will go to the Volt.

As for the Prius PHEV, it looks like with its puny 4.4 kW/hr battery which gives it a meager 6 mile range, it may not be able to limp to the starting line.