The Digital Twin

A digital twin is a live digital representation of a physical asset. It is a cyber-physical mockup that represents both the physical instance and its broad business context in which it operates, from inception to end of life.

The digital twin acts on behalf of connected physical objects by receiving alerts and notifications, sending instructions and updates, and providing real-time information on their state and health to the owners, operators, and maintainers of these assets.

The digital twin is an integral part of the assets’ lifecycle activities. Beyond enabling remote connectivity and control flow, a digital twin must be able to curate a rich decision-making context of a broad spectrum of information and lifecycle activities such as configuration, service entitlement, and maintenance and upgrade history.

Can I Get One, Too?

We usually think of the digital twin as being a digital representation of a physical object, thereby accurately mimicking and predicting the behavior of these objects. But can the notion of a digital twin be expanded to include non-physical entities? Gartner describes the digital twin of an organization as a “dynamic software model of any organization that relies on operational and/or other data to understand how an organization operationalizes its business model, connects with its current state, responds to changes, deploys resources and delivers expected customer value.”

Under that definition, this model is, indeed, a digital twin, albeit confusingly close and perhaps interchangeable with Business Operating System (BOS), and the boundaries and flow between the controlled object and its simulation and governance models are not well defined.

How Many Digital Twins Do You Need?

As organizations explore the potential of connected cyber-physical systems, many seem to be unnecessarily eager to adopt digital twin lingo for every aspect and activity of the product lifecycle. Every digital representation and product information database becomes a digital twin.

They envision multiple digital twins: one during design to provide simulation and prototyping, a manufacturing digital twin connected to the manufacturing line assets, and, of course, the proverbial in-service digital twin to monitor assets in operation and optimize field service operations.

Of course, each of these lifecycle activities: design, manufacturing, and service, will benefit from the enhanced operational insight enabled by a digital twin. But thinking of the digital twin as separate entities along traditional value chain boundaries is incorrect and limiting.

The digital twin utilized during design and prototyping doesn’t disappear when the product goes into production. The information and insight it generated doesn’t become obsolete overnight. And the in-service digital twin cannot operate in isolation; it must leverage information and knowledge created during design and manufacturing.

Thinking about distinct digital twins along the traditional product lifecycle phases misses the point. Worse, it accentuates the inefficiencies most organizations encounter during value chain process transitions.

Older product lifecycle paradigms are crudely separated by value chain activities and the PLM software systems supporting them. There is a distinct—and often difficult—handover from engineering to manufacturing, and an even bigger chasm between manufacturing and downstream operations, after-sales service, and maintenance.

A Trusted Network of Digital Twins

So, no, adding more individual digital twins, no matter how sophisticated, isn’t the answer. Organizations should build a comprehensive digital model that can span all product lifecycle activities.

The digital twin should serve as the central integration point for the multiple stakeholders working on or with the assets throughout the product lifecycle.

Furthermore, product-generated information and PDM-based 3D models and configuration information must be augmented by information and insight from sources that typically reside outside the traditional boundaries of the organizational enterprise software systems. For example, information about inventory levels, competitive products, and market intelligence should be systemized and used in simulations, statistical analyses and machine learning to drive better decision-making.

Of course, these are different disciplines that employ different digital tools and require separate behavioral and decision optimization models. But they must be connected and interacting with each other using the enterprise’s PLM digital backbone.

The connected enterprise facilitates and accelerates the formation of a trusted network of digital twins.

The digitalization of the enterprise’s entire value chain radically redefines how well individual decision makers and the organization understand products and customers, and how they use this wisdom to accelerate innovation, develop new products and service, and optimize existing ones.

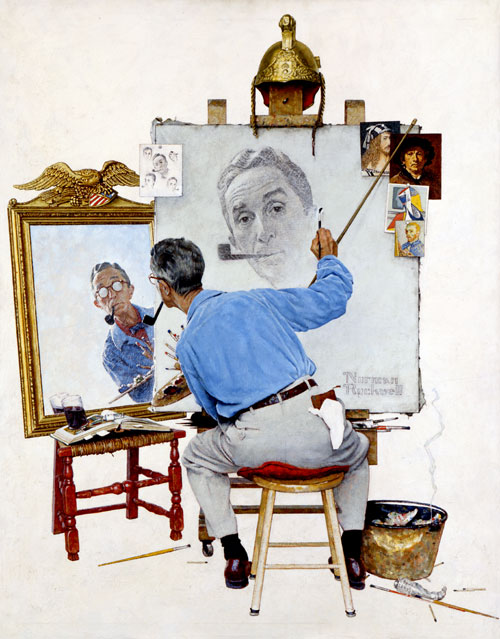

Image: Triple Self Portrait (Norman Rockwell, 1960)