A Bit of Perspective

I want to start this blog post with two personal stories that exemplify the difficulty to provide service personnel highly relevant and effective service information.

Some years ago I was advising a leading industrial equipment manufacturer on various topics related to product service lifecycle management and service operations. We were nearing the launch date of a new machine, but as the project had experienced multiple setbacks and some of the milestone dates had slipped, the service documentation wasn’t going to be ready in time. The product release rules dictated that service information be available at launch time, but delaying the launch for that reason would have been prohibitive.

Management response to the problem was simply to omit certain sections of the service manuals. Traditionally, manuals included a hefty Theory of Operation section, rich with illustrations and photos. To make up for the lost time, the Theory of Operation section was eliminated, and the number of graphic illustrations in other sections was reduced. You can probably guess the end of this story: there was not a single complaint from service technicians about the missing information, nor was there a noticeable degradation in field service performance. Apparently, service technicians did not find this information very useful.

More recently, I accompanied a software vendor on a fact-finding visit to the assembly line of one of Germany’s top automotive manufacturers. Prior to the meeting at the factory, this vendor went to great lengths to describe new software for authoring and delivering assembly work instructions. But lo and behold, when we went on the assembly line floor, there was not a single document—paper or electronic—to be seen. The reason? The technicians on the assembly line perform routine—albeit very complex—tasks and very rarely, if ever, need technical information beyond the initial training and their continued experience.

Service Manuals

Technical publications and service manuals have always been the backbone of service operations, describing how a piece of complex equipment works and fails, how to isolate the roots cause of the failure, and how to effect the appropriate repair action using troubleshooting flowcharts and fault isolation procedure.

Over the years, many technologies have been recruited to assist in creating and delivering technical information. From time to time, emerging technologies such as expert systems and knowledge based systems even attempted to replace the traditional document-based methods completely, to no avail.

Yet, the fundamental challenge facing tech pubs authors hasn’t changed: how to produce relevant and effective information that helps service technicians deliver effective, efficient and safe maintenance and repairs.

From Documents to Service Communications

In my previous blog post Service as a Knowledge Intensive Activity, I discussed the reasons why product and service knowledge is diminishing and, increasingly, service technicians lack the necessary diagnostics and repair information to perform their job effectively.

As the examples is the beginning of this article demonstrated, much of the traditional service information content given to technicians, such as theory of operation, does not deliver the anticipated results. Furthermore, other studies show that even when additional information is needed, many technicians prefer to consult a peer rather than use service documentation (and even the help desk), resulting in further erosion of trust and usage of company provided technical information.

What do Technicians Really Need?

Let’s start by looking at what service technicians don’t need. They do not need fancy tools, as dazzling as they might be, to assist them in performing routine tasks. This is probably the first faux pas committed by many misguided software vendor. (The second one assumes that technicians are so ill-prepared that they need a heavy duty 3D CAD viewer to navigate through the entire product structure in order to perform a simple remove-and-replace operation. And no owner of a broken equipment wants to see the technician wasting time “flying through” the equipment just to perform basic service.)

The key to delivering useful service information is giving the service technician fresh information that represent the most recent cumulative knowledge of the organization. This information should focus less on generic information and common knowledge that technicians already possess (although a reminder might not hurt) and more on the task at hand.

Specifically, service information needs to be product and task specific: the equipment’s “as-maintained” configuration, its operation and maintenance history. As importantly, it should provide the most recent updates and lessons learned, and up-to-date organizational knowledge that can be retrieved and applied in the singular context of the equipment serial number, the symptom being diagnosed, and the repair to be performed.

Restating the Case for Theory of Operation

In this and previous blogs post I repeatedly made the case against documenting what I referred to as routine service incidents. This is a good place to discuss this point again and propose a broader perspective on the topic.

While the principal point is still relevant and authoring generic information and routine service instructions is often a waste, it’s important to acknowledge that there are circumstances that service technicians, even the more experienced one, do need this type of information.

I previously discussed some of the technical and business causes for the attrition in service experience and expertise. These are especially pronounced in industries that produce low volumes of uniquely configured products. Manufacturers of build-to-order and configured-to-order products, such as trucks, mining equipment, construction machine and agricultural equipment report that technicians seek “basic” information such as schematics and remove-and-replace procedures to help them fix a piece of equipment hey have never worked on before.

Service information and PLM

There is a tight relationships between service communication and PLM. Service knowledge and knowledge communication tools such as training, service information and technical support must be tightly coupled with product lifecycle to ensure a constant linkage between product lifecycle changes and the corresponding service information.

Treating service information as part of the product bill of material (BOM) and managing it inside the PLM cycle will improve the accuracy of service information, accelerate deployment of updates, and reduces the cost of authoring and delivering service information.

What about Advanced Service Technologies?

I mentioned earlier some alternative methods and technologies that emerge from time to time and appear to threatened the traditional document-oriented service communication practices. The 80s saw numerous expert system technologies come and go, followed by a wave of knowledge management tools that didn’t last very long. More recently, hardware oriented technologies: wearable devices, augmented reality, and the Internet of Things (IoT) also suggest to propel the state of the art in service operation forward.

Whether you agree with the hype or not, these past and present technologies are means to ensure service technicians have ready access to the most recent task-specific service information. So here we are, back to the starting point: service is a knowledge intensive activity, and service communication tools and processes must ensure technicians have access to the most accurate and up-to-date corporate knowledge, technical information and job aids.

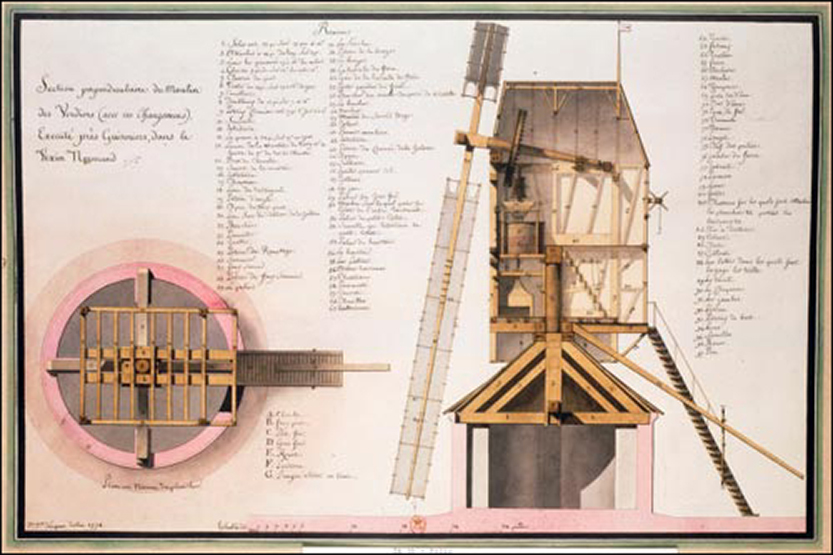

Image: Section perpendiculaire du moulin des Verdiers (Jean-Jacque Lequeu, 1778)